Allow me to introduce the trihydrogen cation, H3+. It's created in certain low pressure environments from plain old molecular dihydrogen. Firstly, you need to knock an electron out of a H2 molecule like so;

Allow me to introduce the trihydrogen cation, H3+. It's created in certain low pressure environments from plain old molecular dihydrogen. Firstly, you need to knock an electron out of a H2 molecule like so;Cosmic rays** are the best way of doing that. Mainly because they're everywhere and there are a lot of them. That H2+ molecule will then react with the first thing it collides with, and the first thing it collides with is usually another unsuspecting H2 molecule. Then this happens;

Voila. One H3+ molecule -- one of my favourite little molecules, and the subject of a lot of intense study by a number of extremely intelligent people. It's even been referred to as "A Beautiful Jewel of Nature." H3+ is a fascinating molecule for a number of reasons. For one, it has some rather unusual chemical bonding. In school we're all taught the rule that there are two types of chemical bond. Ionic bonds between positive and negative ions, and covalent bonds where two atoms share two electrons. As with so many rules in chemistry though, this rule can be bent. Electron deficient molecules like H3+ exhibit 3-centre-2-electron bonding. Which is exactly what it sounds like it should be. The three atomic nuclei are bonded together by only two electrons between them all. In this case, being as there are 3 hydrogen nuclei, the electrons distribute themselves evenly across the entire molecule. Weirdly, this means that there aren't three separate bonds in this molecule. The best description really is one single bond spread across three atoms!

As a result, H3+ is rather weakly bound together. Hydrogen is much more comfortable as a H2 molecule and it'll do its best to get rid of one of those atoms and and be that way, if it can. It'll leave a H+ behind on virtually any molecule it encounters, and because a H+ is simply a proton, the reaction is known as "protonation". Incidentally, this is why H3+ is destroyed almost instantly at higher pressures. It only takes one collision to destroy it. In the air that you're breathing, thousands upon thousands of collisions between molecules are happening every second. The effect is that H3+ is a potent "protonating agent" which sets off a chain reaction of interstellar ion-molecule chemistry.*** For instance, supposing H3+ was to collide and react with an oxygen atom;

The oxygen steals a proton, and leaves a hydrogen molecule to go off about its business elsewhere. This gives an OH+ molecule, which will happily react further with more hydrogen;

OH2+ + H2 → OH3+ + H

If at any point, one of these molecules were to absorb a stray electron (like the one kicked off that hydrogen molecule right back at the start), it'll break it apart like a fortune cookie. All of that energy needs to go somewhere, and in small gaseous molecules, it's just too much. The molecule can't dissipate it all quickly enough, so the bond falls apart with all of that energy. This has an interesting effect when an electron is absorbed by one of those OH3+ molecules;

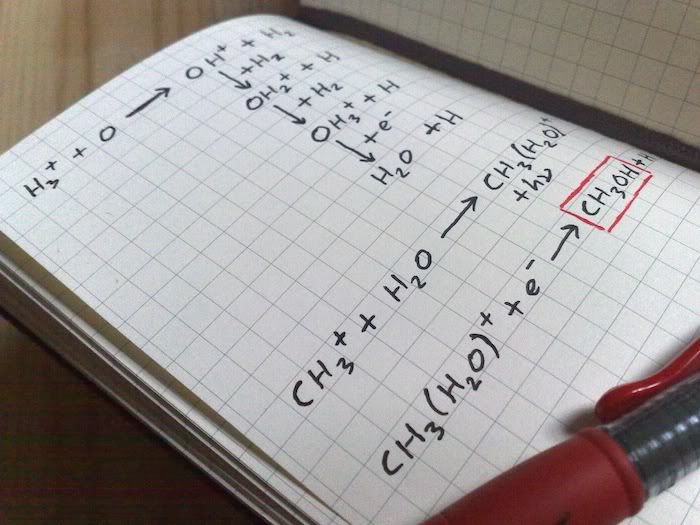

And there you have it. H2O. Water. The third most common molecule in the Universe. This H3+ initiated reaction is how water is formed in interstellar space. Pretty cool, huh? Similar H3+ reactions happen to all sorts of other things, from carbon atoms to large polyatomics. But I've talked enough chemistry for one day. Instead, I'll leave you with a page from my notebook. CH3OH, by the way, is methanol, and as any radio astronomer will tell you, methanol too is seen almost everywhere in interstellar space.

*Welcome to the zooniverse, where all your dreams come true... niverse.

**Incidentally, a cosmic ray isn't actually a "ray" at all. They're particles. Mostly they're protons or sometimes α-particles, travelling at ridiculously high velocities. With such speed comes energy, such that a cosmic ray barely even noticed the fact that it's ionised a molecule. A bit like a subatomic hit-and-run, if you will.

***Technically speaking, H3+ is one of the most powerful acids known for just that reason. That's all a classical acid is -- a molecule which donates a proton to another molecule.

No comments:

Post a Comment